The False Narrative of Growth vs Value Investing

Cambiar SMID Value and Small Cap Value Portfolio Managers tackle the ongoing debate between value and growth.

Should value and growth be thought of as mutually exclusive?

Absolutely not. Is it hot or is it sunny? Is she a CFA Charterholder or a good stock picker? Is the car red or is it fast? While these are obviously not mutually exclusive choices, when it comes to investing, we believe the growth versus value debate has fully decoupled from basic logic, venturing into the deeply misleading. In the very simplest of terms, “growth” is a characteristic specific to a company’s fundamentals. “Value” is a characteristic of the company’s stock price. In fact, “growth” is an input in the academic framework for determining the “value” of a company, as it should be.

As an active value manager, how do you identify various intangible measurements that create the alpha thesis for investments aside from the traditional value metrics?

When it comes to investing, we believe the growth versus value debate has fully decoupled from basic logic, venturing into the deeply misleading.

“Value” has historically been defined in the context of a company’s book value, dating back to Benjamin Graham’s writings 70+ years ago. Graham’s writings remain foundational and are far more insightful than anything we can produce, but as with all ideas, we feel they must evolve over time. The reality is book value-oriented measures remain relevant for a subset of companies that require capital to operate and grow. In today’s knowledge economy where intellectual property (IP) is critical, we believe accounting book value alone simply fails to offer much guidance in determining what a business is worth.

We assess the fundamentals of a company, including its product strength, market position, profitability, cash generation, balance sheet, and growth opportunities to determine what we believe to be a fair price for those characteristics. For the same reason you might be willing to pay more for an iPhone with tremendous utility vs a flip phone with relatively less, we assign a higher value to a company that boasts above-average marks on the characteristics above. A better business may be more “expensive”, but it could be a better “value”, all things considered. Those may seem like obvious observations, but the current industry standard of categorizing stocks and portfolios as value or growth seems to cause a choice between characteristics and absolute price.

What is your take on the current style divergence between the value and growth indices?

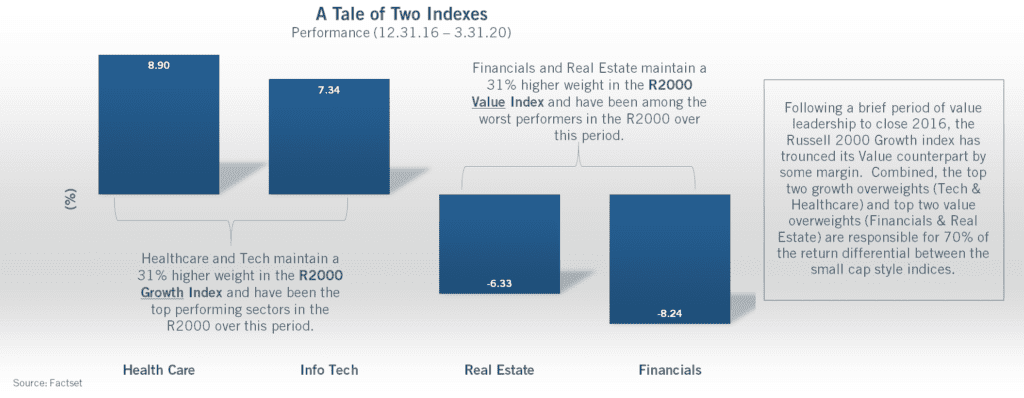

We believe the discussion of value’s underperformance versus growth is poorly framed. Part of what is really happening when the value index lags the growth index is the stock prices within the industries that dominate the value benchmark are failing to keep up with those in the sectors more prominent in the growth index (See Small Cap example below). While the latter group might trade at a higher absolute multiple, there also tends to be more unique, IP centric value-added businesses that convert that position into higher profitability, more consistent free cash flow, and ultimately growth potential. As with the phone analogy, there is a price to pay for those superior characteristics that might be above the more homogenous businesses inherent in the less differentiated industries that dominate the value index. That higher price does not mean they are not value stocks, as some industry standards are biased toward suggesting.

Categorizing stocks, portfolios and indices by style has been a foundation of the investment community for decades. Does this practice remain appropriate or are there issues investors should be aware of?

Fund evaluation service providers, such as Morningstar and Lipper, employ elaborate formulas for assigning a growth or value score to individual stocks which informs the overall skew of a portfolio. They examine various measures of stock valuation and company fundamental growth to rate a holding’s value and growth characteristics. Whichever attribute is more extreme tends to drive the stock’s categorization. While this looks like a thoughtful approach, it yields certain biases and does not capture the type of unique situation an active value investor should be pursuing.

Say a company had a growth rate of 500% and a PE of 14x. In this case, the standard assessment criteria would likely consider this a growth stock and not a value stock, when any fundamental investor would consider this among the best values in the market. Though extreme, it frames the problem of simplistic models that force a choice between growth and value.

Should consultants continue to use style boxes and value benchmarks when deciding their asset allocations/rebalance strategies?

Even the most basic due diligence into the value versus growth dynamic suggests current benchmarks (and style boxes) are not measuring value properly. For example, book value multiples and dividend yields are meaningful parts of a company’s value score. This inherently biases the value score away from asset-light companies or those that do not pay much of a dividend. Many technology and healthcare companies fit this profile, but this does not exclusively make them growth stocks.

The following Morningstar table of the Cambiar SMID Value strategy is particularly instructive:

| Value vs Growth Measures | |||

| Cambiar SMID Value | Russell MidCap Index | Morningstar MidCap Blend Category | |

| Price/Prospective Earnings | 12.40 | 19.70 | 19.26 |

| Price/Book | 1.53 | 1.93 | 1.66 |

| Price/Sales | 1.43 | 1.32 | 1.17 |

| Price/Cash Flow | 7.14 | 8.37 | 6.96 |

| Dividend Yield (%) | 2.64 | 2.23 | 1.96 |

| Long-Term Earnings (%) | 10.56 | 8.86 | 9.67 |

| Historical Earnings (%) | 18.53 | 9.30 | 11.75 |

| Sales Growth (%) | 8.96 | 6.11 | 4.77 |

| Cash-Flow Growth (%) | 14.84 | 4.95 | 5.89 |

| Book-Value Growth (%) | 10.14 | 6.14 | 6.37 |

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of 3.31.20. Forward-looking metrics are based on historical data.

Morningstar categorizes Cambiar SMID Value as “blend” – in the middle of value and growth. Yet in this very table, the portfolio shows better long-term earnings, sales, cash flow, and book value growth than our peers and the index, at a P/E discount of 37% and 36%, respectively. While this observation discounts some of the other valuation measures where we are more in line or at a premium, we think PE, as a proxy for free cash flow, is the most important as free cash flow has been the best performing value factor over time. This is a simplistic snapshot and much more bottom-up analysis goes into assembling our portfolio than those metrics, but we believe it serves to provide some perspective on the discussion.

In allocating client capital, we suggest consideration for how the underlying manager assesses value. At Cambiar, we think the price one pays is critical in driving above-average forward returns. Value managers can be too obsessed with near term absolute levels of PE while missing the enormous value creation potential if a financial model could just correctly assess performance beyond the immediate term, perhaps in forward year 3 and beyond. For instance, one of the biggest market cap stocks of them all, Amazon, traded at a seemingly nose bleed 35x trailing free cash flow at year-end 2016, but only 16.5x the amount ultimately produced just three years later while still growing the top line 20%+. Was Amazon a growth stock in late 2016 that value managers should not touch, or would a more accurate financial forecast have correctly identified Amazon as being reasonably valued at that time?

What has Cambiar been doing of late, and how have Cambiar’s domestic strategies performed generally through the value chasm and periods of excessive volatility in recent years?

Our long-held bottom-up research process at Cambiar continues to first and foremost focus on identifying great businesses we want to own. Businesses with a structurally advantaged product or market position consistently converted into top line growth, above-average margin and returns, and robust and growing free cash flow. Businesses with conservative balance sheets as excess leverage and reliance on the capital markets can jeopardize the long term potential of a strong business for minority equity holders. We believe accumulating a portfolio of superior, value-creating companies trading at a discount to fair multiples with many different sources of return across the holdings, should yield attractive capital appreciation opportunities over rolling 3 and 5 year periods while proving more durable in times of stress.

While it is easy to say the above, we are proud that we have been able to marry our stated strategy for stock selection and portfolio construction with strong performance within our domestic portfolios. We have confidence our approach will deliver attractive returns over the long run and wish to remain a predictable allocator of capital on behalf of clients.

To learn more about Cambiar’s suite of domestic offerings, please visit the following pages:

Thank you for taking the time to hear our thoughts on assessing value and growth. We appreciate your continued confidence in Cambiar Investors.

Certain information contained in this communication constitutes “forward-looking statements”, which are based on Cambiar’s beliefs, as well as certain assumptions concerning future events, using information currently available to Cambiar. Due to market risk and uncertainties, actual events, results or performance may differ materially from that reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. The information provided is not intended to be, and should not be construed as, investment, legal or tax advice. Nothing contained herein should be construed as a recommendation or endorsement to buy or sell any security, investment or portfolio allocation.

Any characteristics included are for illustrative purposes and accordingly, no assumptions or comparisons should be made based upon these ratios. Statistics/charts and certain other information may be based upon third party sources that are deemed reliable; however, Cambiar does not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. As with any investments, there are risks to be considered. Past performance is no indication of future results. All material is provided for informational purposes only and there is no guarantee that any opinions expressed herein will be valid beyond the date of this communication.

Data is provided for a representative account as of March 31, 2020. Portfolio characteristics change over time and may differ between clients based upon their investment objectives, financial situations and risk tolerances. Cambiar makes no warranty, either express or implied, that the weightings shown will be used to manage your account. The securities presented do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold, or recommended by Cambiar and the reader should not assume that investments in the securities identified were or will be profitable. The information provided on the page should not be considered a recommendation to buy or a solicitation to purchase or sell any particular security. There can be no assurance that an investor will earn a profit or not lose money. There can be no assurance that the portfolio will continue to hold the same position in companies described herein, and the portfolio may change any portfolio position at any time. As with any investments, there are risks to be considered. Past performance is no indication of future results.

Russell Midcap Index: The Russell Midcap Index is a market capitalization-weighted index comprised of 800 publicly traded U.S. companies with market caps of between $2 and $10 billion. The 800 companies in the Russell Midcap Index are the 800 smallest of the 1,000 companies that comprise the Russell 1000 Index.